Again, in an effort to embrace the intersectionality between Black History Month and Disability History, here is a brief look at the remarkable life of Brad Lomax.

Few have done more to advocate Black Americans and the Disabled than Brad Lomax. Lomax was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis while in college after having fallen a number of times. As his condition progressed, he needed to use a wheelchair and began to see the world from a different perspective.

He helped form the Washington chapter of the Black Panther Party in 1969 in an effort to free Blacks of inequality, police brutality, and poverty, all of which were prevalent in the US in the late 60s. In 1972, he helped organize the first African Liberation Day demonstration on the National Mall in D.C., drawing thousands to show solidarity with African nations attempting to gain independence.

The following year he moved to Oakland, CA, a hotbed for activism for those fighting for disability rights and other marginalized groups. Oakland would be the place where he would face many challenges, but also see his greatest successes. He grew frustrated trying to navigate the Oakland transit system where his brother had to carry him from his wheelchair up the bus steps to a bus seat and then retrieve his wheelchair, something Lomax found degrading. He saw firsthand that disabled people lacked access to public buildings that had no ramps, were often denied access to education, faced enormous challenges finding housing or jobs, and received very little in the way of support and services, all of which was far worse for Blacks with disabilities.

Lomax started working with the Center for Independent Living (CIL) and Ed Roberts (Foreshadowing hint: you’ll learn more about Roberts in an upcoming profile). He suggested that CIL work with the Black Panthers to focus on assisting East Oakland’s Black disabled community. It wouldn’t be the first time they would work together.

Providing access to healthcare, jobs, education, and public buildings was met with a lot of political resistance in the mid 70s due to the fear of costs, enforcement, and leaving the government open to lawsuits. Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 was supposed to allow access to public buildings, but no actual regulations were published so it was unenforceable. After years of attempted litigation and protests around the country, activists took over the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) offices in Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Denver, Los Angeles, New York City, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Seattle, and Washington, D.C. on April 5, 1977. HEW oversaw Section 504 and had been dragging its feet on codifying actual regulation suggestions meant to give it teeth, and make it enforceable. This occupation of numerous government buildings became known as the 504 Sit-ins, conceived by Frank Bowe (more foreshadowing hints).

Within days, only the San Francisco sit-in remained active. In the other occupation locations, activists were either driven out by the government cutting electricity or running water to the buildings, or had to vacate the premises due to a lack of food and supplies. Lomax had worked with his friends in the San Francisco Black Panther Party to provide food, medicine, and supplies to the activists there. Without that support, many experts say San Francisco would not have had the impact it had and likely would have wound up ending their occupation early like the other locations.

On April 28, HEW caved. Due to pressure from the sit-in in San Francisco, access to public buildings became easier for everyone. Section 504 was the most important legislation for disabled Americans until the passage of 1990’s Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), and there is no doubt the success of the 504 Sit-in helped pave the way for the ADA. The 504 Sit-in was the longest takeover of a federal building in US history.

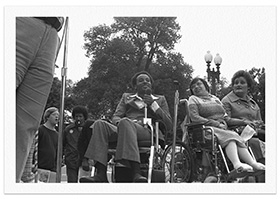

Lomax and a handful of others left the occupation of HEW’s office to travel to D.C. for the signing of the regulations to strengthen Section 504. He returned to HEW’s San Francisco office on April 30 and left with his fellow occupiers, with many singing “We Shall Overcome.”

He died in 1984 due to complications of multiple sclerosis.

For more information on Brad Lomax, Section 504, the 504 Sit-ins, and the Crip Camp documentary, please check out the following:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brad_Lomax

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/504_Sit-in

keep them coming! ❤️

LikeLike

Excellent read CHRIS! Thank you for sharing 🙏❤️

LikeLike